Matthew Lanyon

Painting Textiles Drawing

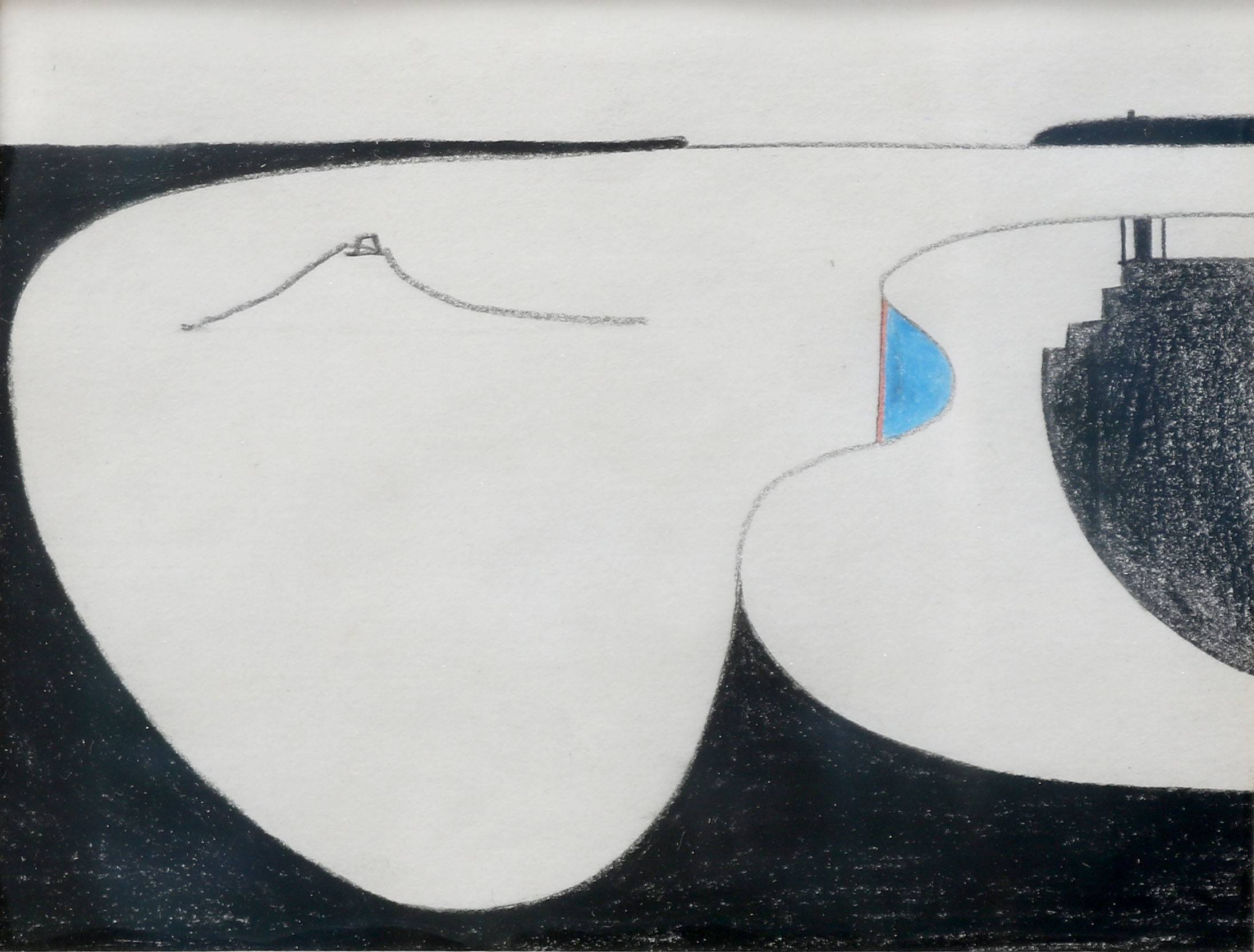

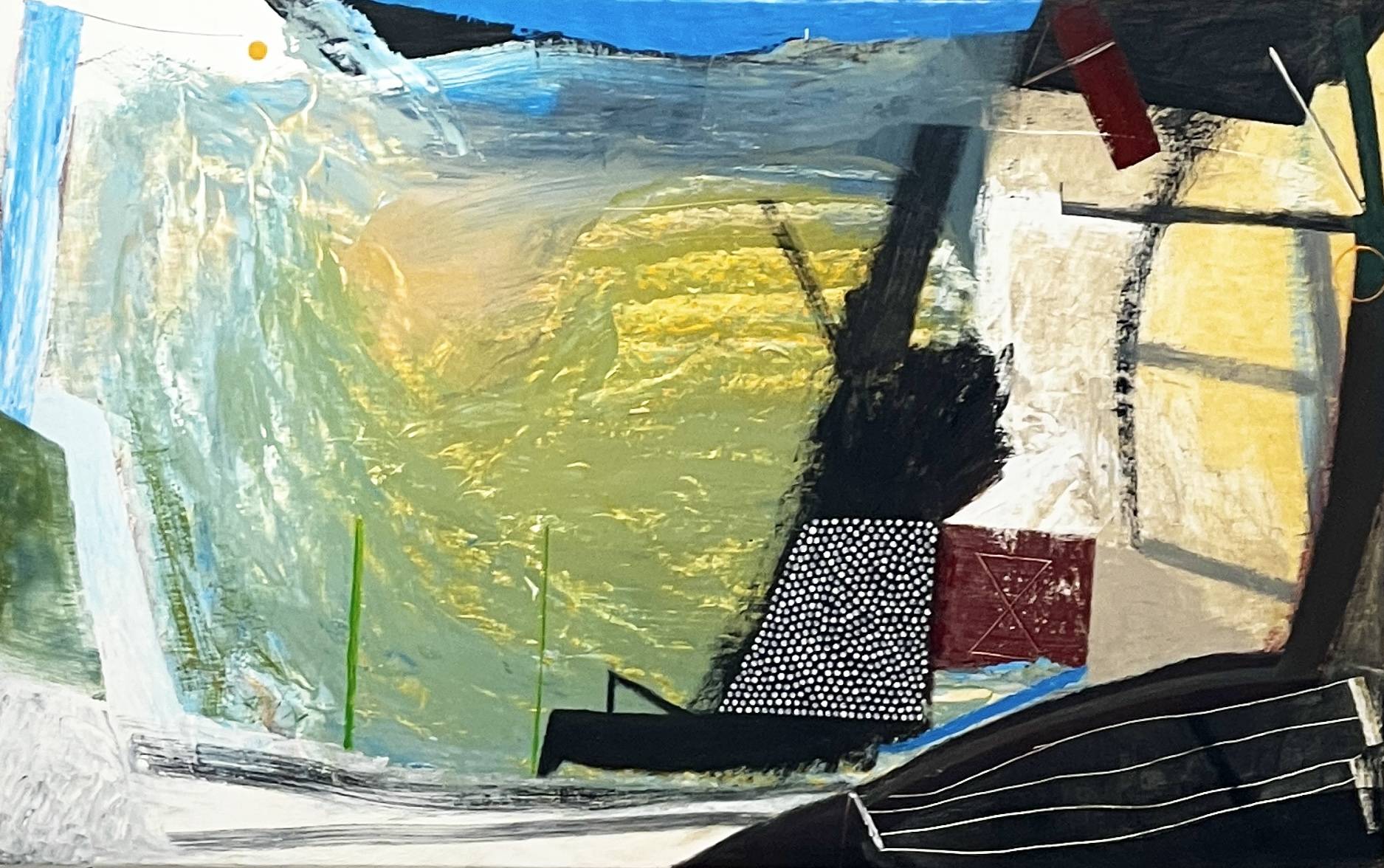

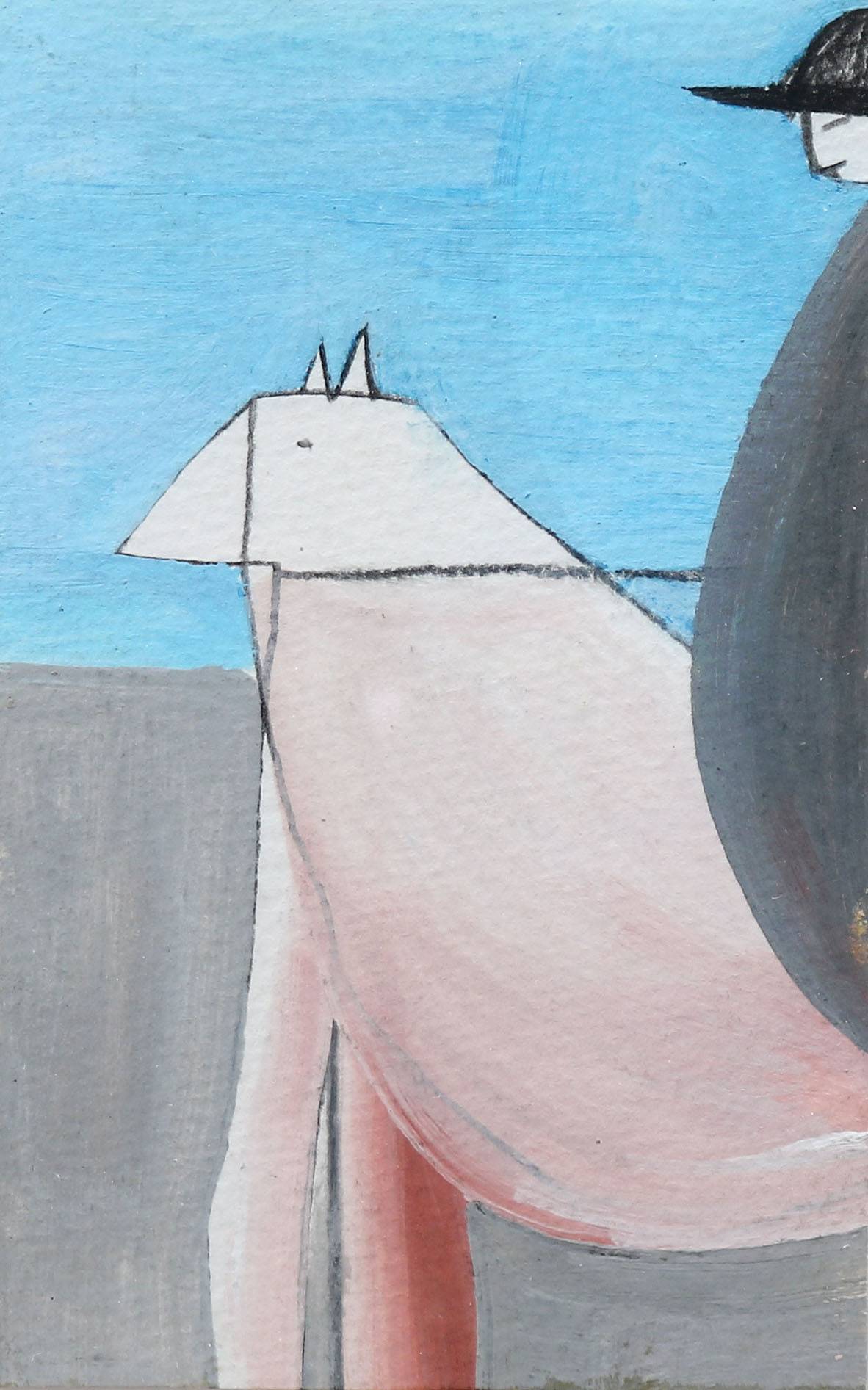

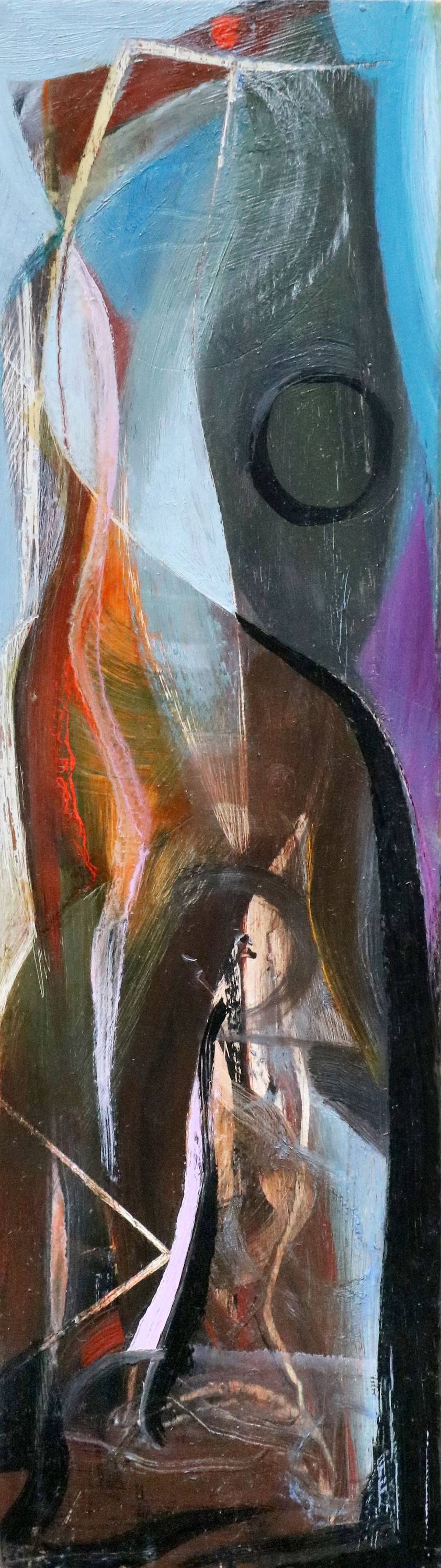

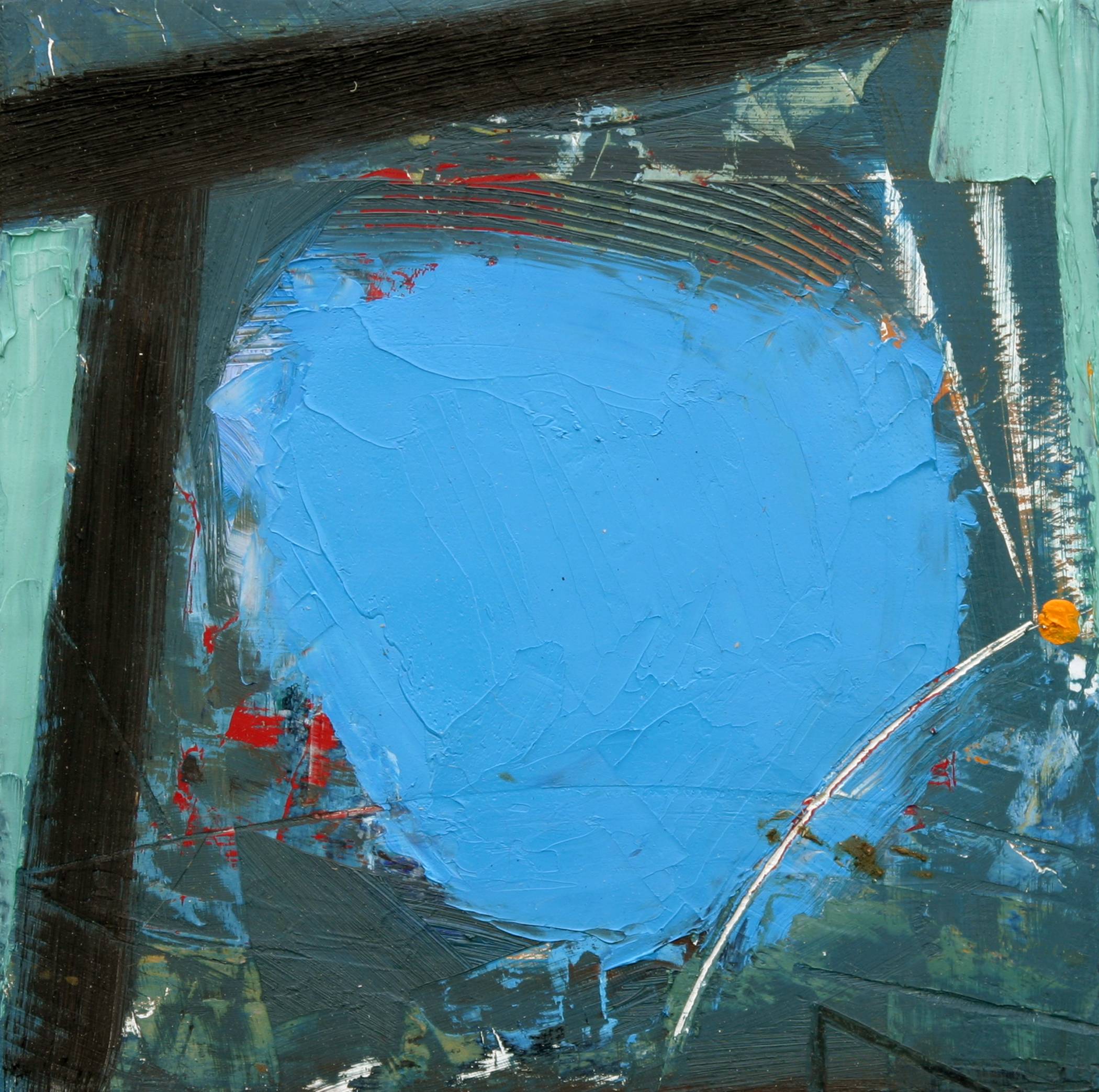

Matthew Lanyon (1951 - 2016) is considered one of Cornwall's most important artists. His paintings, tapestries, screenprints and assemblages employ an exclusive visual language created by the artist over his lifetime. Using this invented set of signs, his deeply allegorical works explore pattern and abstraction in the context of the history and landscape of Cornwall's West Penwith, where he was born and raised.

Please contact the gallery for available works

Matthew was born in St Ives, Cornwall in 1951, one of the six children of Modernist painter Peter Lanyon. He attended Port Regis and Bryanston School, Dorset, and later Humphrey Davy Grammar School, Penzance. In 1964, Matthew’s father, Peter Lanyon, died as the result of a gliding accident, an event which had a profound effect on Matthews life, and later his career as an artist. In his twenties Matthew studied at Leicester University, starting originally with Geology and Psychology, but later moved on to the History of Science, Archaeology and Linguistics. He spent the first part of his career working on building sites as a carpenter and joiner, and it was not until he was approaching his forties that he began to focus on making artwork.

His first major solo show, at the Rainy Day Gallery in Penzance in 2007, included a painting seven metres long entitled Journey to the Stars. Over his career he continued to push the scale of his paintings towards the truly monumental and began to experiment with architectural glass and tapestry. His final exhibition, In the Tracks of the Yellow Dog, was held at the New Craftsman Gallery in St Ives in September 2016, the same month that Matthew died. New Craftsman also held a retrospective of his work, titled Faster than Words, Older than Thought, in 2018.

Selected Exhibitions:

2018: Faster than Words, Older than Thought; New Craftsman Gallery St Ives, solo show;

2017: Uillinn, West Meets West, West Cork Arts Centre, three man show;

2016: Falmouth City Art Gallery – mixed;

New Craftsman Gallery – solo;

2015: Porthminster Gallery – solo;

2014: Porthminster Gallery – mixed;

New Craftsman Gallery – solo;

2013: Porthminster Gallery – mixed;

Porthminster Gallery – solo;

2012: 18/21 Gallery – mixed;

Porthminster Gallery – mixed;

Open Space Gallery – mixed;

New Craftsman Gallery – solo;

Hilton Fine Art – mixed;

2011: Bohun Gallery – mixed;

Porthminster Gallery – mixed;

Open Space Gallery – mixed;

New Craftsman Gallery – solo;

Wetpaint Gallery – mixed;

2010: Porthminster Gallery – mixed;

Rainyday Gallery – solo;

Gloss Gallery – mixed;

New Craftsman Gallery – two man;

2009: Porthminster Gallery – mixed;

Rainyday Gallery – solo;

Tutti arts gallery – mixed;

Bohun Gallery – mixed;

2008: Porthminster Gallery - summer collection;

Rainyday Gallery – solo;

2007: Tate St. Ives;

Rainyday Gallery – solo;

Porthminster Gallery;

The John Davies Gallery;

2006: Minster Fine Art – Solo;

New Grafton Gallery;

The Rainy Day Gallery – solo;

The John Davies Gallery;

2005: Wiseman Originals, London;

Rainyday Gallery, Penzance – solo;

Minster Fine Art, York - solo ;

2004: The John Davies Gallery, Stow-on-the-Wold;

Wiseman Originals, London;

Rainyday Gallery, Penzance – solo;

The Hutson Gallery, London;

Platform 100 Exhibition, London;

Affordable Art Fair, London;

2003: Rainyday Gallery, Penzance – solo;

2002: Badcocks Gallery, Newlyn – solo;

Affordable Art Fair;

2001: Rainyday Gallery, Penzance – solo;

Wiseman Originals, London;

2000: Rainyday Gallery, Penzance.

I was born in St Ives, Cornwall in 1951, one of six. My father was Peter Lanyon - a landscape painter who became a major figure in the world of art. After the war St Ives had become a centre of the modern movement in abstract art and my father was commissioned to produce the painting Porthleven for The Festival of Britain. His mentors were Naum Gabo and Ben Nicholson. While I was tearing round the garden as Davy Crockett, movers and shakers of art were passing the sugar and spreading the cream. Shortly before he died in 1964, as the result of a gliding accident, we spent some days together in his studio making a model aircraft. We made prototype wings out of polystyrene and tried to strengthen them with muslin and glue-size. Years later I read what someone had written about his painting Clevedon Night, which had these two prototype wings attached to the canvas. They might be 'boats bobbing up and down' but I knew what they were. They weren't boats. But it doesn't matter whether this was true or not. That isn't the point - we read our own life into paintings. A few days with him in the studio, a few days camping out in the Thames van on Perranporth Airfield and he was gone. I was thirteen. He was forty-six. His death came into me like an ocean.

It was not until 1988 that I began to take my artwork seriously. At that time I was drawing and painting every morning with my son, in the days before he went to school. He always had the best titles. I'd ask him about one of his drawings and he'd say with the absolute sincerity of a four-year-old, 'Three Cows Walking on the Water'. Between my father and my son I had begun to address the problem of what anything is, or is meant to be in a painting. If cows could walk on water and bits of polystyrene that were once wings can bob up and down like boats, then painting is alive and the better for being marginalised by all the exquisite distractions of sound and movement.